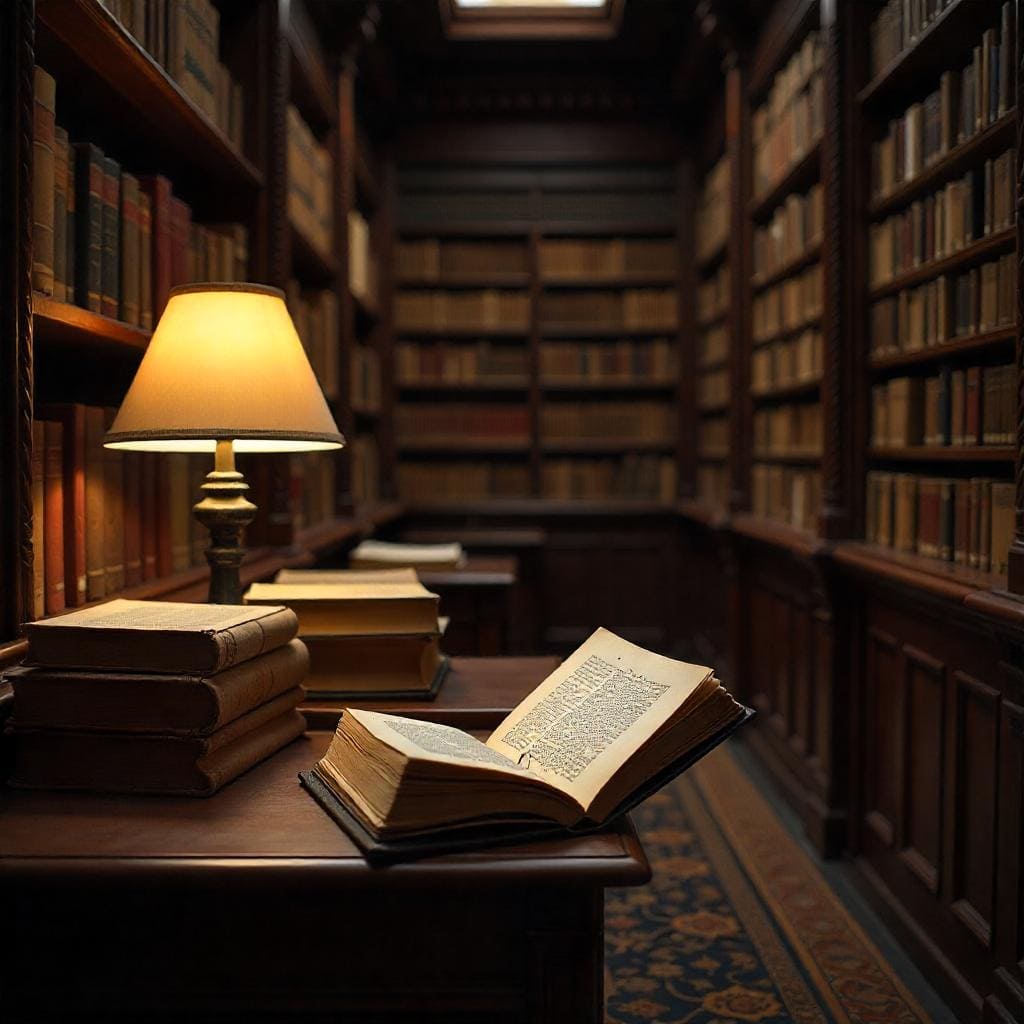

Language is more than just a tool for communication—it’s a living museum of human history. Every word we speak carries echoes of the past, preserving the triumphs, struggles, and daily lives of those who came before us. From ancient trade routes to forgotten empires, the evolution of language reveals how societies interacted, clashed, and merged over centuries. Etymology, the study of word origins, acts like an archaeological dig, uncovering layers of meaning that connect us to distant cultures and eras. Whether it’s a borrowed term from a conquered civilization or a phrase born on the battlefield, language holds stories waiting to be decoded.

Think about the words you use every day. The English language alone is a patchwork of Latin, Germanic, French, and countless other influences—each layer reflecting a historical turning point. Idioms like “by the skin of your teeth” or “the writing on the wall” have roots in ancient texts, while seemingly mundane words like “salary” (from Latin salarium, or “salt money”) reveal how economies once functioned. In this post, we’ll explore how language serves as a time capsule, preserving the beliefs, innovations, and even the humor of generations long gone. By understanding the hidden histories in our speech, we don’t just learn about words—we rediscover the people who shaped them.

1. Etymology: Unlocking the Past Through Words

Etymology—the study of word origins—is like linguistic archaeology, digging through layers of time to uncover how language evolves. By tracing a word’s journey across centuries and continents, we reveal hidden connections between cultures, migrations, and historical turning points. Etymology doesn’t just tell us what words mean; it shows us how people lived, traded, fought, and dreamed.

1.1 The Roots of Language

Every word has a birthplace. Etymology maps these origins, showing how languages branch from common ancestors or absorb foreign influences through conquest, trade, and cultural exchange.

- Latin’s Living Legacy: Over 60% of English words have Latin or Greek roots, a testament to the Roman Empire’s enduring influence. For example:

- “Government” (from Latin gubernare, meaning “to steer”) reflects ancient metaphors of leadership.

- “Money” (from moneta, an epithet for Juno, whose temple housed Rome’s mint).

- Proto-Languages: Linguists reconstruct lost languages like Proto-Indo-European (PIE), the mother tongue of everything from Sanskrit to Spanish. The PIE root dʰewbʰ- (“deep”) gave us “depth” (English), “dubok” (Russian for “deep”), and “dubh” (Gaelic for “dark”).

These connections aren’t just academic—they’re threads in the fabric of human history.

1.2 Words as Historical Artifacts

Words are cultural fossils. Borrowed terms reveal who traded with whom, who conquered whom, and which ideas crossed borders.

- Trade Routes in Vocabulary:

- “Coffee” (from Arabic qahwa) entered European languages via Ottoman Turkish, marking the spread of the beverage from Ethiopia to global obsession.

- “Sugar” (from Sanskrit śarkarā) traveled through Persian (shakar) and Arabic (sukkar) before reaching medieval Europe.

- Conquest and Power:

- The Norman invasion of England (1066) flooded English with French terms like “beef” (from boeuf), while Anglo-Saxon peasants raised “cows” (from Germanic kū). The words we use for food still reflect medieval class divides.

These borrowed words are more than vocabulary—they’re records of encounters that shaped the world.

2. Idioms and Sayings: Frozen Moments in Time

Idioms are linguistic time capsules, preserving long-lost customs, technologies, and worldviews. Unlike literal language, these phrases often resist translation because their meanings are tied to specific historical moments.

2.1 War and Conflict in Everyday Phrases

Many idioms were born in violence, freezing battlefield realities into everyday speech.

- “Bite the bullet”: In the 19th century, soldiers undergoing surgery without anesthesia clenched a bullet between their teeth to endure the pain.

- “Crossing the Rubicon”: When Julius Caesar led his army across the Rubicon River in 49 BCE, he defied Rome’s laws—making conflict inevitable. Today, it means passing a point of no return.

- “Throw in the towel”: From boxing, where a coach literally threw a towel into the ring to concede defeat.

These phrases keep history alive in our conversations, often without us realizing it.

2.2 Nautical and Exploration Terms

The Age of Exploration left a sea of idioms in its wake, many still used by landlocked speakers.

- “Under the weather”: Sick sailors were sent below deck (under the weather side) to recover.

- “The whole nine yards”: Theories range from WWII fighter pilots’ ammunition belts (9 yards long) to the fabric needed for a Scottish kilt. The mystery itself reflects how history obscures origins.

- “Loose cannon”: A literal hazard on wooden ships; now a metaphor for unpredictability.

Even in the digital age, we speak in relics of wind and sail.

3. Cultural Memory in Language

Language is a living archive of human experience, preserving traces of civilizations long gone and social attitudes that have evolved over centuries. Words act as tiny time capsules, carrying forward fragments of lost worlds into modern speech. Whether through surviving terms from extinct languages or subtle shifts in what we consider polite, our vocabulary reveals how societies remember—and sometimes forget—their past.

3.1 Lost Civilizations in Modern Vocabulary

Some words are among the last surviving remnants of cultures that have otherwise vanished from history.

- Isolated Language Survivors:

- Basque (Euskara), Europe’s last pre-Indo-European language, gives us words like “izquierda” (Spanish for “left,” from Basque ezker). Its persistence hints at a lost pre-Celtic Europe.

- Etruscan, the mysterious civilization that ruled Italy before Rome, survives in a few loanwords like “person” (possibly from Etruscan phersu, meaning “masked ritual actor”).

- Indigenous Loanwords:

- “Tomato” (from Nahuatl tomatl) and “chocolate” (from xocolātl) are culinary gifts from the Aztec Empire.

- “Kayak” (Inuit qajaq) and “moccasin” (Algonquian mockasin) preserve Indigenous technologies in everyday English.

These words are more than borrowings—they’re quiet monuments to cultures that reshaped the modern world.

3.2 Taboos and Euphemisms

Language often bends around what societies fear or find uncomfortable, leaving behind clues about historical anxieties.

- The “Bear” Paradox:

- Germanic tribes avoided saying the sacred animal’s name (berô), using instead “bear” (meaning “the brown one”). The original term was lost—but survives in Greek “arktos” (hence “Arctic”).

- Latin had no such taboo, giving us “ursine” from ursus.

- Death and Decency:

- “Passed away” (19th-century gentility) replaced blunter terms like “died.”

- Victorian euphemisms like “limb” (for “leg”) reveal how morality shaped even basic vocabulary.

Taboos fade, but their linguistic footprints remain, showing how culture molds speech.

4. Language as a Record of Social Change

Language doesn’t just reflect history—it evolves with it. Shifts in gender norms, technology, and power structures leave indelible marks on how we speak, turning vocabulary into a mirror of societal progress (or regression).

4.1 Gender and Power in Word Histories

Many common words carry hidden assumptions about gender and authority.

- Medical Misogyny:

- “Hysterical” (from Greek hystera, “womb”) reflected the ancient belief that women’s emotions stemmed from a “wandering uterus.”

- “Nurse” (from Latin nutrire, “to nourish”) remains gendered despite male practitioners.

- Titles and Status:

- “Mrs.” (from “Mistress”) originally denoted female authority, but was restricted to married women, while “Mr.” applied to all men.

- The push for “Mx.” (gender-neutral) continues this evolution.

These changes show language struggling to keep pace with social justice movements.

4.2 Technology’s Impact on Language

Every technological revolution rewires vocabulary, repurposing old words and minting new ones.

- Repurposed Terms:

- “Dashboard”: Once a board on horse carriages to stop mud (“dash”), now a digital interface.

- “Wireless”: From early radio to Wi-Fi.

- Digital Age Coinages:

- “Meme” (from Greek mimema, “imitated thing”) was reborn online.

- “Ghosting” (abruptly cutting contact) reflects the anonymity of apps.

Tech doesn’t just add words—it changes how we think about communication itself.

5. Preserving History Through Linguistic Study

Language is humanity’s oldest archive—one that doesn’t just record history but actively shapes it. By studying how words evolve, disappear, or are reborn, linguists and historians piece together the puzzle of human civilization. From reconstructing ancient proto-languages to fighting language extinction, these efforts don’t just preserve words—they safeguard entire worldviews, technologies, and ways of being that would otherwise vanish forever.

5.1 The Role of Linguists and Historians

Linguistic detective work allows us to hear echoes of unwritten histories.

- Proto-Languages as Time Machines:

- By comparing modern languages, linguists reconstruct ancestral tongues like Proto-Indo-European (PIE), spoken over 6,000 years ago. The word “wheel” (PIE kʷékʷlos) appears in Sanskrit (chakra), Greek (kúklos), and Old English (hwēol), revealing how its invention spread with migrating cultures.

- The Finno-Ugric family (including Finnish and Hungarian) hints at ancient Uralic migrations now lost to archaeology.

- Unwritten Histories in Grammar:

- The Aboriginal Australian language Guugu Yimithirr uses cardinal directions (north/south) instead of “left/right,” suggesting a culture deeply attuned to landscape—a worldview preserved only in speech.

These reconstructions turn vocabulary into a map of human movement and innovation.

5.2 Endangered Languages and Cultural Loss

A language dies every two weeks—and with it, a unique understanding of the world.

- Why It Matters:

- The Tofa language of Siberia has 30 words for reindeer hides, encoding knowledge critical for survival in the taiga. Without it, the community loses both identity and ecological expertise.

- Yuchi (Oklahoma) uses verb forms that distinguish firsthand vs. secondhand knowledge—a grammatical reflection of cultural values around truth.

- Revival Against the Odds:

- Hebrew: Revived from liturgical use to a living language with 9 million speakers, proving “dead” languages can breathe again.

- Māori: New Zealand’s kōhanga reo (“language nests”) raised child fluency from 5% to 50% in 30 years by immersing preschoolers in the language.

- Wampanoag: Linguist Jessie Little Doe Baird reconstructed her ancestors’ tongue from 17th-century documents—now spoken by children for the first time in centuries.

Conclusion

Language is more than a tool for communication—it’s a living record of human history, preserving the triumphs, struggles, and daily lives of those who came before us. From the echoes of ancient trade routes in borrowed words to the societal shifts embedded in evolving idioms, every phrase we use carries fragments of forgotten worlds. The study of etymology and linguistic preservation isn’t just academic; it’s an act of cultural archaeology, uncovering how migrations, power dynamics, and technological revolutions have shaped the way we think and speak. As languages vanish and others are revived, we’re reminded that words are not just vessels of meaning but guardians of memory—each one a thread in the vast, interconnected tapestry of human experience. To lose a language is to lose a piece of history, but to understand its journey is to keep that history alive.

“What linguistic artifact in your native language or dialect offers the most profound insight into your cultural or historical identity?”